Sadly, we have been surrounded by talk of death for nearly a year. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an estimated 3.19million people died in the U.S. in 2020, quite a bit more than the 2.85 million in 2019, and at 9.7 deaths per 1,000, last year was the highest rate since 1949. Pre-pandemic, the Census Bureau did not project this level of deaths until 2029.

The medical community has been very careful not to conflate the world of medical examiners and the organ donation industry. Notwithstanding that there are nearly 110k people on organ transplant lists according to the Centers of Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), or that there are approximately 500k unexplained deaths each year that require some level of post-mortem examination, it has been a third rail issue to directly link the two worlds. The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) has delicately concluded that organ donation has not meaningfully compromised autopsy evidence, and therefore, subsequent criminal proceedings.

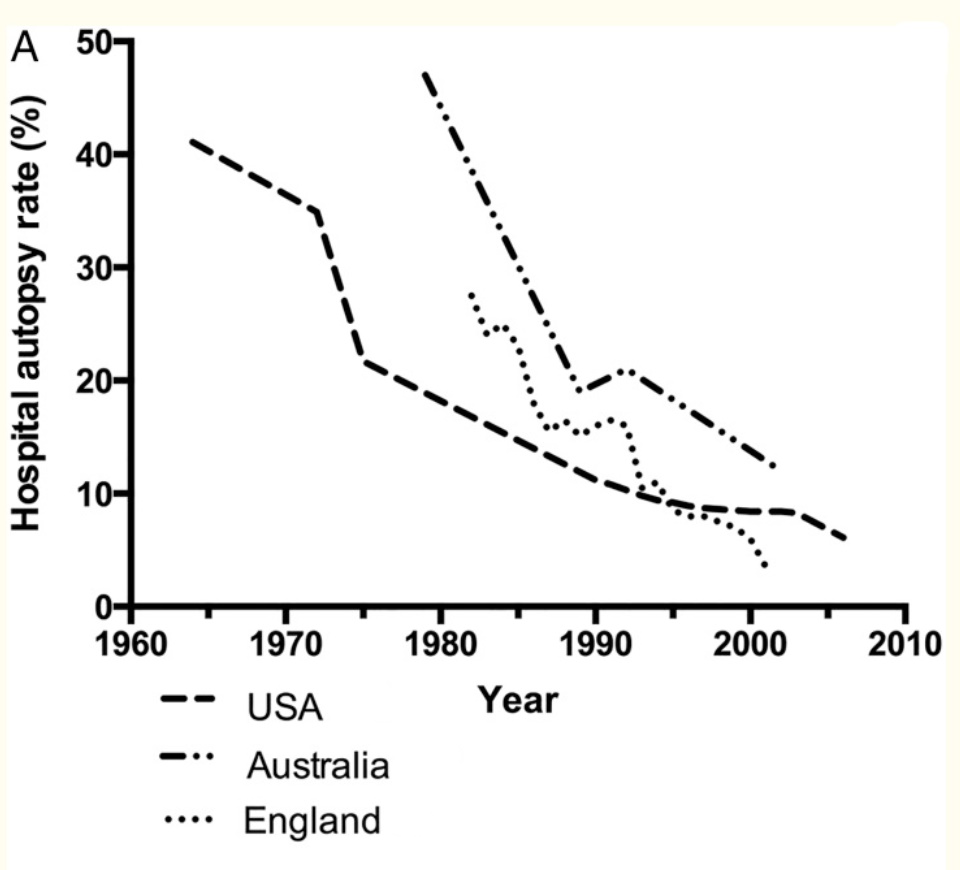

It is hard to make money with death. There are no billing codes for autopsies. Hospitals typically extract from the Medicare Part A basket for a “variety of services” which includes autopsies. In fact, hospitals are not obligated to provide autopsy services nor are they typically reimbursed by private insurance or Medicare. Notably, CMS determined in 1986 that autopsies were not considered “patient care” and therefore, would not be covered. The average cost of an autopsy ranges between $3,000 – $5,000, but can be as much as $10,000, depending on how comprehensive the analysis. It gets even more complicated – upon death, in the eyes of the law one ceases to be a “person” but rather “property” which can trigger a debate about chain of custody. All of this has resulted in the rate of autopsies to collapse.

It is estimated that less than 5% of all deaths have a proper autopsy by a medical examiner (versus coroner who may either be a lay person without clinical training or other healthcare provider). According to the National Association of Medical Examiners, which has less than 1,000 members (see below), there is an acute shortage of trained examiners, who are spread thinly across 68 offices around the country. While the reasons for this are numerous, low pay (~$150k per annum) and social stigma rank high on the list. Medical schools do not actively promote this discipline.

Irrefutably, autopsies are an essential component of an effective public health infrastructure, from understanding the spread of disease, effects of pollution and drug use, to bio-terrorism; all brought even more so into focus by the Covid-19 pandemic. According to a recent Journal of the American Medical Association study, an estimated 25% of all autopsies discovered a major diagnostic error (although this may be trending to be less than 10% per more recent studies). More troubling, according to a 2005 report by the International Academy of Pathology, approximately one-third of all death certificates identified causes of death that were not suspected prior to death and that more than 20% of those unexpected findings could have only been determined histologically. Furthermore, it is estimated that 10% of all cases had antemortem diagnostic errors.

Recall the early days of the pandemic and the extraordinary levels of confusion over the numerous and varied symptoms. Was it a respiratory syndrome? A circulatory condition? Given that there are effectively no autopsies performed in China, early insights were hard to come by, delaying a more complete understanding of the disease progression. Obvious concerns about infection and transmission severely limited the number of completed autopsies in many U.S. hospitals.

As the pandemic progressed into the summer and fall of 2020, medical examiners started to elucidate issues around prolonged ventilator use and lung damage, as well as observing microscopic lung clots missed by other imaging modalities. It was not for several months after the pandemic’s onset that the systemic attack of the coronavirus became more apparent. Unfortunately, the question “did someone die with Covid or from Covid?” is still for many unanswered.

There is a misperception among many, exacerbated by the glorification of the field by CSI or Grey’s Anatomy, that technology has dramatically improved the accuracy and speed of autopsies. Notwithstanding the advances promised by “virtual autopsy,” improved computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging, 3-D surface scanning, and Lodox (low-dose, digital x-ray scanning), it is still true that smell and eyesight are the most effective tools utilized by medical examiners. The National Institute of Justice does acknowledge that big data analytics, multi-modal imaging, and augmented reality have meaningfully improved the ability to profile and reconstruct crime scenes which inform autopsies.

Very separate but related, technical advances have materially improved the organ transplantation field. Globally, the World Health Organization estimates that 150k transplants are performed annually (40k in the U.S. alone) and that 1.5 million people today have transplanted organs. Advances in hepatitis testing and better surveillance systems alone have dramatically increased the number of potential donors.

While the first transplant procedures were done with dogs in 1902, it was not until 1954 that the first human organ transplant operation was successfully performed (after developing effective immune suppression therapies). Today there are more than 250 transplant centers that coordinate with a national organ registry. Recent CMS rules promulgated in November 2020 seek to clarify under what conditions Organ Procurement Organizations (OPO) may be reimbursed, bringing much needed certainty to the field, and hopefully reducing the 20 preventable daily deaths for those waiting for available organs.

These rules also attempt to address significant racial disparities around organ availability and access. It is believed that the rules will also encourage greater donation rates while improving a registry’s ability to match viable organs with appropriate recipients. There are 58 OPOs today which coordinate securing consents, managing transportation logistics, and the clinical needs of the donors.

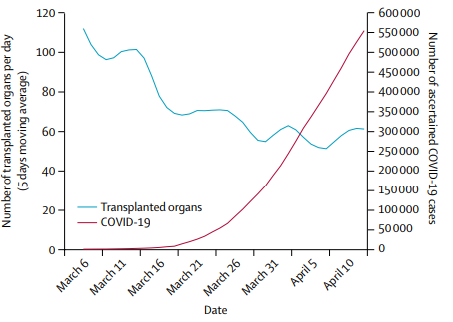

Obviously, for many hospitals, transplantation volumes dropped materially along with many other procedures due to Covid, while some stand-out organizations have seen an increase in case volume. Intermountain Healthcare, based in Utah, saw record organ transplant volumes due in part to its utilization of tele-visit platform to better assess patients and commitment to robust surveillance systems.

None of this is cheap. A kidney transplant is likely to cost upwards of $400k, while a heart transplant is estimated to cost $1.3 million, with on-going monthly bills of $2,500 for anti-rejection therapies (see Fortune’s 2017 estimates below). This begins to introduce a series of more troublesome issues such as how to handle a “free market” for organs and the precise determination of when someone has died.

A controversial 2013 essay by noted economist, Gary Becker at the University of Chicago, posited that monetary incentives for organs would materially eliminate the long transplant list while only increasing the costs of donated organs by 12%. He goes on to conclude that the price for a kidney would be approximately $15k and a liver would be $32k.

Juxtapose that to the illegal black market for donors; in 2009 the FBI broke up an organ trafficking crime syndicate, which was sourcing kidneys, mostly from Pakistan, the Philippines, and China, for street prices up to $160k. The Chinese Deputy Minister of Health in 2007 acknowledged that nearly 95% of organs were “sourced” from executed prisoners. More compliant donors are thought to receive upwards of $10k for a kidney. This is a supply chain fraught with profit margin issues. It also has introduced the concept of “transplantation tourism” as recipients have been known to travel overseas for such procedures, but that often introduces numerous other health issues.

While a few organs can be donated from someone who is alive, many require the donor to be either brain dead or considered dead by circulatory death. Obviously, this ushers in another host of ethical debates – what is the definition of death? How are consents managed? As flagged earlier, there are real issues surrounding chain of custody and ownership of someone’s body who has passed. Medical examiners can only determine how someone died and is not looked to determine if someone is actually dead.

Where these worlds tragically collide is around murder rates, which increased nearly 40% in 2020 in the U.S.’s top ten cities. This dramatically reverses a general trend of declining murder rates since the early 1990s and is compounded by notable declines in “clearance rates” to solve these murders. In these same cities, clearance rates declined 7% last year to 59%; the rate of murders in Chicago increased 55% in 2020 and now has a clearance rate of only 46%. Surprisingly, Las Vegas solves 94% of its murders. In general, lower clearance rates are in part attributed to so many people wearing masks.

Sadly, there was one other disturbing study released last year by the New England Journal of Medicine which tracked 700k first-time gun owners from 2004 to 2016. Evidently, in that group, men and women are 8x and 35x more likely to commit suicide, respectively. A closer look at the data exposes that first-time gun owners are 100x more likely to commit suicide in the first month of firearm ownership (which tails down to 2x by the twelve year). Over the six months prior to the November 2020 election, background checks for gun purchases increased 50%. Suicide is horribly complicated and tragically is often a source of donated organs.

If you have any thoughts of self-harm or suicide, please pick up the phone right now and call the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 1-800-273-8255

Pingback: Autonomous Vehicles vs. Bad Drivers… | On the Flying Bridge